Few contemporary poets can be said to “contain multitudes,” as Walt Whitman did. Mark Rudman is one of them, as evidenced by his Rider quintet, which culminates in Sundays on the Phone. The winner of numerous prizes (The National Book Critics Circle Award, the Max Hayward Award for a translation of Boris Pasternak, and numerous fellowships), Rudman has been widely praised for his work, which manages to be ambitious and intimate, harrowing and funny. When his last book, The Couple, was published, Harold Pinter commented that Rudman had “woven an extraordinarily rich and highly original tapestry. It’s an impressive achievement.” Thom Gunn wrote of Rider (1994), the quintet’s first volume, that it was “The most believable book I have ever read about love.” An exceptionally well-read writer, and as much a cultural commentator as a writer of poems, Rudman has won some of the highest awards. His work, written in a seamless blend of verse and prose, the traditional and colloquial, documentary and personal, combines elements of biography, lyric, conversation, essay, and asides. Yet he remains, in the best sense, a poet’s poet, and it may well be the wide-ranging, discursive element of his poetic – which requires more than the brief investment of time allotted by so many readers – that has so far precluded his work from gaining the wider audience that it so richly deserves. This seems particularly true now, since Rudman’s control of the demotic and of the multiple themes of class, race, poverty, and privilege, has reinvigorated an art that often appears remote from public concerns and the polis. Here is a poet who confronts suffering, and is himself engaged in a poetic salvage operation through which he is able to transform anger (that which embittered his mother and caused his father to commit suicide) into energy. Rudman has evolved an autobiographical epic of surprising emotional and intellectual power. Surveying his output over the last decade, one gets the feeling that his achievement will soon garner wider recognition.

Rudman’s method has diverse antecedents. Denis Diderot and Edmond Jabès have been mentioned by reviewers before (and there is a short piece on Jabès in Diverse Voices, Rudman’s 1993 book of essays). Rudman’s mercurial, colloquial verse dialogue that crosses metaphysical boundaries recalls James Merrill; and the cinematic touches – voice over, concise director’s notes, asides, digressions – bring to mind the Pasolini of “A Desperate Vitality.” Dialogic verse that ranges from high diction to low dates from Dante, Shakespeare, and Whitman, but Rudman has also translated Euripides, and written adaptations (‘palimpsests’) of Horace and Ovid. He is acutely aware that to work in language is to work with freighted material, and has remarked that “the American poet is often deluded by the fantasy of not being weighed down with antiquity, of having an opportunity to encounter history anew without an overlay.” The classics are the model par excellence for reimagining the family and individual as the striated site of civic morality, and Rudman shares a talent for translation – and for the transposition of classical examples – with Frank Bidart and C.K. Williams, two elder contemporaries. The classics have also been formally rejuvenating for Rudman: “I found that modernism was implicit in Horace, with his sudden leaps, allusions, reversals, turnings, and complex use of form and sound based on Greek models [...] Horace’s sudden leaps to another plane were prophetic of catastrophe theory.” In an essay entitled “Catastrophe Practice” in his 1995 book of essays, Realm of Unknowing, Rudman appraises Nicholas Mosley’s writing as a strategy of fragments, intuitively sequential and capable of acknowledging the simultaneity and transhistoricity of subjective time. Rudman’s point is that Mosley’s style allows for a closer representation of how the mind works – sometimes stimulated to move ahead by the sudden shocks of catastrophe, other times immobilized by known limits, half-measures, the conditioning past. “Stammerers stammer because they can’t render what is in the mind – the larger picture, lost unity – in sequential speech. The stammerer has not repressed the awareness of how little of what comes out ‘for all its lovely cadences (perhaps because of them?)’ has to do with ‘what is going on in one’s head.’” Rudman’s writing similarly implodes chronological narrative; it is the record of an obsessive recapitulation of the past alongside attempts to live in the present. In “The Night,” an essay on Antonioni in Realm of Unknowing, Rudman defines the concept of duration as “moments of perception which take consciousness a long time to detail, to populate. Consciousness can never unravel all that it perceives happening in an instant.” The Rider quintet responds to such moments of limitless duration, which rise to consciousness in the poetry through fragmentary and elliptical narratives.

In Sundays on the Phone, the voices of the poems range from Anita O’Day to the local dentist to the members of Rudman’s immediate family; the voices of the departed mix with those still among us, to comic and harrowing effect. The speakers we hear most often are the poet’s stepfather, the poet himself, and the poet’s mother – whose complexity, and complexes, dominate the volume. Poems refer to one another, threads of conversation are taken up again, and dialogues don’t seem closed at book’s end – which is fitting, since Rudman’s project is to lay bare the subject’s self-fashioning. One could say that his subjects are the testing-ground for the health of the American body politic. And Rudman’s is a body politic saturated in the language of jazz and film. An epigraph to “Fragile Craft” in the quintet’s previous book, The Couple, quotes Michael Powell: “Cinema is the mythology of the twentieth century.” Rudman is an avowed ‘burrower’ – an obsessive collector of popular culture – and he has a knack for juxtaposing the armature of daily life with the mythological stories that typically pass for the ephemera of our imagination. For example, when Rudman leaves a notebook behind on a plane, it is salvaged from the deep by Aesacus the Diver (from Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book XI, and reworked in the trio of Aesacus poems in the quintet’s second book, The Millennium Hotel), who then passes it on to Andromeda (Metamorphoses, Book IV, and “Perseus and Andromeda” in The Couple) – who in turn restores something of its contents to the author. The voices of this poem, “Sons and Lovers Recovered!,” which report what is retrieved from the notebook, belong to the notebook itself; to the ‘rider’ of the quintet’s first book – alternately prickly, empathetic, and discursive; and to Andromeda, who concludes the discussion by apprising Rudman of the multiple delusions attending his youthful obsession with Mary Ure. The notebook spoke of the poet’s mother taking him, at age 11, to see 'Sons and Lovers' – “a real / adult film, no one else’s mother in town like that would have taken their child to see...” – and, having completed the transmission of the notebook’s meditation with these lines:

I know it saddens you Mark to think how companionable

your mother had been and could be in light of

how she became and even though I am only

antimatter now—not even graph

paper—

it saddens me too!

You—who wrote on me in such a way that I felt wanted… …

Yours Truly,

Lost (Moleskin) Graph Paper Notebook

Andromeda writes:

PS

Dear Mark,

Let me clarify a few points. It was Ure’s strength you liked; it was only her blond hair and pale complexion that made you remember her as ethereal. It is not she who is fragile but the actor’s craft. It’s the same subliminal mistake Perseus made when he saw me chained to the rock and he watched the wind lash my hair across my face. But he was just a boy, like Paul Morel.

Do you know that the parts you like best in the film weren’t even in Lawrence’s novel?

Yours truly,

Andromeda

The finer memories the poet has of his childhood are just as suspect – and indelible – as his experience, as an eleven-year-old in 1960, of the film rendition of Sons and Lovers. As in the example above, Rudman’s poems often juxtapose the ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’; voices and time frames recur over the course of the quintet, creating a vortex through which the reader follows the poet toward an eventual understanding, if not reconciliation. And despite the inclusive method of the quintet, Sundays on the Phone is akin to Rider, its bookend partner, in that it is paradoxically a work of remarkable focus and economy – the battle lines are sharply drawn, the speakers are precise, lines are brief and sentences pointed, and even poems of several pages’ length are works of concision.

Rudman’s probing of the relationship between mother and son is at the center of the book. Marjorie Louise Levy Leeds Harris Rudman Strome – one person – died in 1999. By the end of Sundays on the Phone, the reader can almost construct her biography, particularly as it is lived under the oppressive influence of male figures: her father, who scorned Marjorie’s artistic ambitions while cultivating those of her brother (the filmmaker Herbert Leeds); and her husbands, both alcoholics. Some of Rudman’s most powerful work has addressed his father – “rebarbative, even in death” (“Dreams of Cities,” in Realm of Unknowing) – and his stepfather, interlocutor from beyond, uncommon voice of sanity amidst family chaos, and the ‘rider’ of Rider. In Sundays on the Phone, we learn about Marjorie’s life in her own words or through overheard dialogues between mother and son. Rudman’s own son, Samuel, figures in these poems from the beginning; as Samuel matures into his teenage years, the poet’s empathy grows for his late father, mother, and stepfather, though his anguish does not diminish. On closing the book, we understand why “Back Stairwell” describes the poet, “the last of the parents / who don’t send a stand-in […] propelled by a kind of demon” as he runs up the synagogue stairs to pick up his son from day care; shortly thereafter, Samuel responds with “a look of sheer defiance” when his father tries to get him to hold onto the banister:

the same boy who, the other night

I watched shuffle and backpedal and nearly fall,

down the escalator, over

the rapids of the raw-toothed

edges of the blades;

his hands, his attention, occupied

by a rabbit samurai Ninja turtle

and Krang, the bodiless brain.

I gauged the dive I would need

to catch him if he fell:

a flat out floating horizontal grab

I couldn’t even have managed in my youth.

The daily terror of being a parent – of endlessly striving to give one’s own child the best of oneself – is all the more poignant for this poem’s position at the volume’s outset, as a deceptively casual sign of what follows.

At times – as announced in the frontispiece, “The Nowhere Water,” originally published in The Nowhere Steps (1990) – the relationship between mother and son is blissful and effortless; at others it is painful for everybody involved – mother, son, and then grandson. At the time of Sundays on the Phone, fifteen years after The Nowhere Steps, all of Rudman’s parent-figures are deceased. The struggle of living with (or on the phone with) his mother has ended, and it is as though he can see “Marjy, Left to Her Own Devices,” the title of one of the book’s prose pieces. An abruptly direct passage from that poem glosses the entire volume:

My point: she was younger than her years and, as every word written in this book attests, she was born too early (as well as in the wrong family) to have the choice to live a life in which she would have flourished, even if her temperament and sense of unwantedness was the same as it was. There are a lot of functioning, successful people who are not happy in their personal lives but they take satisfaction from their work. My mother “could have been” (for instance), to use a modest example, an art historian, transforming her encyclopedic knowledge into a vocation. She could have spent her days in a wish-come-true factory, surrounded by and immersed in images and objects from another time.

Following his mother’s death, there is clarity: Rudman is witness to the fall of a family, his mother’s brother dead by his own hand, and his mother consumed, eaten alive by anger because trapped in an unrewarding existence light years from how she envisioned life with a ‘Rabbi.’ Yet this clarity delivers the poet into an impasse, dark as those he has observed in others who have written of spiritual conversion; the volume’s final poem, “Conversion in Scafa,” finds him stuck deep in a wordless melancholy, unable to express himself without pain and collapse. But Rudman is heir to the skeptical pragmatism of the American diaspora; what redemption might be on offer, the poem implies, is here and within us, if we have the courage to observe carefully:

But this July in the rugged Abruzzo something stole my sleep.

In exhaustion, it all comes clear.

The stars so close to the ground.

The way, the way they appear, one by one.

No vasty, vertiginous blur.

The dry, ravaged air that molds

every rock and shrub and crevice and grotto,

every white house chiseled into the Apennine range.

Not that there is no secret to the universe,

but that the secret may not be one

we want to hear.

At the conclusion of Rider, the poet was “set free” by the empathy of a preacher and hospice worker, who came to love Rudman’s stepfather Sidney, ‘the little Rabbi,’ during their time together. At the end of Sundays on the Phone, equilibrium is restored in a renewed quest for metaphysical knowledge. The poems resist closure – and the quintet likewise – because they are the embodiment of a life lived according to the dictates of a persistently dialectical mind. For years, mother and son had spoken by phone on Sunday morning. Sunday no longer threatens with phone calls – but it wouldn’t be correct to say there’s no one on the other end of the line.

Review of Mark Rudman, Sundays on the Phone (Wesleyan UP, 2005), by Nick Benson, in Prairie Schooner 82:1 (Spring 2008).

Tuesday, April 29, 2008

Wednesday, April 23, 2008

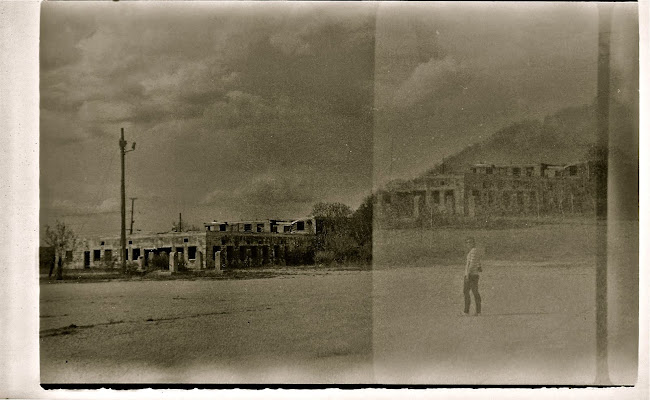

Interview with Photographer David H. Wells

The photographer David Wells visited us (he travelled from Providence on his Suzuki) and gave a presentation & visited classes on April 15th. Ian has now finished viewing All The President's Men and transcribed the bulk of his discussion with David, which follows.

David Wells came to The Gunnery on April 15th and gave a presentation of his photographs. Mr. Wells was born in Albany, New York in 1956, and has a Bachelor of Arts in the Liberal Arts from Pitzer College of the Claremont Colleges. He is a commercial photographer, photo-essayist, and photo-educator based in Providence, Rhode Island. His work has been published and shown in exhibitions around the world and he has received two Fullbright fellowships among several other prestigious grants.

Last things first: what advice would you give young aspiring photographers?

The answer is always the same. When I started out if you could expose film well and use a camera well you could get work, because not many people could do it. So as time went on people learned how to do black and white, so I started doing color and more and more sophisticated stuff because people couldn’t do it. The problem is digital has vaporized the whole craft question – anyone can do it. Then it becomes what is it that you can bring to it that no one else can. Is it style? For example, a lot of wedding photography is about relationships and portraits, and about customer service people liking you. If you’re doing food photography you have to be a great cook. If you’re doing nature photography you have to know your subject as well as you know photography. The photography part is completely sort of presumed. So the question is what do you do that somebody else doesn’t do that makes you different. And that is true of anything. Fashion, portraits, food, anything. So that’s the advice I’d give anybody: figure out what makes you different. If I was doing it again, I would study languages, simply because if there’s a hundred of us lined up and you speak Spanish or Chinese, you’ll get the job. I’d also maybe study anthropology or economics. Anything but photography really. The craft part isn’t want you should spend your four years in college on. Maybe spend it on language, anthropology, psychology, economics, political science, history, economics, maybe business so you know how to market yourself, but not on photography.

How’d you get involved with newspapers?

Well I was at a college, I had worked briefly in an art gallery and I abhorred it, I wanted to do something more stimulating. So I started rooting around to get a newspaper job. Back then – and I think this might still be true – newspapers were continually testing you to see if you’d screw up. I think the first newspaper job I ever got paid money for was to go down to the animal shelter to photograph a dog they were trying to adopt away. And if you could photograph a dog without screwing up, they give you another assignment and another assignment, continually testing you, and if you got to a certain point without screwing up they gave you a real job. That’s exactly how I started. Now it’s a bit more formal, you can get a degree in it.

What did you go to college to study?

History of photography. My mother wasn’t convinced; parents don’t generally look at photography as a career. So I studied history of photography and I learned a lot and a lot of what I talk about in all my classes – about how you look at a photograph and how your eye travels through a photograph and what makes a photograph work – all that came from studying history of photography. I apply that when I’m out taking photographs. I couldn’t have made a career out of it though, being a historian of photography, without going to graduate school, and I didn’t have the money at the time, so I became a photojournalist.

When did you first start taking pictures?

1972 in High school. I was failing French class in high school and I needed a class to transfer into. It was then called Industrial Arts; it’s Shop now. We did some photography in that and I didn’t really like the drilling holes, but when you put the paper in the chemical and the image pops up, I liked that. I had a very good teacher for it. I wasn’t very good at academic subjects so I did everything I could to hang out in the darkroom. He gave me a lot of leeway and I didn’t screw up, and one thing led to another and he ended up teaching me ninety percent of what I know. For me that was very pivotal.

Where do you think you’ll go next in your work?

I have no idea. The problem is it’s completely dependent on someone paying me. There’s no money coming in right now on future work, so I don’t know if it will go on hiatus or I’ll do it on my own. I’ve just started talking with a writer and I think we’re going to start focusing on Bangalore, where my wife’s family is from, and where most of the change you saw taking place in my photographs is happening.

I think we’ll do something on the changing urban landscape, the way Bangalore is being built and rebuilt is what we’ll focus on. If I can get funded I want to keep going on it. I’m also very interested in pursuing multimedia projects like the rickshaw piece that was shown during the slideshow.

I think we’ll do something on the changing urban landscape, the way Bangalore is being built and rebuilt is what we’ll focus on. If I can get funded I want to keep going on it. I’m also very interested in pursuing multimedia projects like the rickshaw piece that was shown during the slideshow.[Thanks to David Wells for permission to reprint the photo above.]

Friday, April 11, 2008

Interview with Valzhyna Mort

Ms. Mort had met Dylan Crittenden earlier in the day, and arranged for him to introduce her reading with a song.

Dylan Crittenden singing Im wunderschönen Monat Mai (Robert Schumann's setting of a poem by Heinrich Heine) at the reading (below).

Ms. Mort embarked on her busy schedule leading writing workshops and visiting classes with the following interview with Ian Engelberger.

Ian: What’s your main inspiration when writing?

Mort: Everything. I cannot have one source of inspiration - if I had one source of inspiration it would be very easy for me to write, because I would just use and reuse such a wonderful source. But there’s no source. A wonderful Polish poet and Nobel laureate in poetry, Czeslaw Milosz, said that poets are the secretaries of the invisible. This is how I’d like to describe myself. I really sort of feel the same way.

I: How do you begin to write your poems?

M: I started when I was eighteen. I came to literature from a music background. I was studying to be a professional musician but then I quit because I was sixteen and stupid. I was looking for the music in my life because I really liked it and in school we began studying the Belarusian language, because I came from a Russian speaking family. The language was very musical, and that was sort of my way of writing music in a language. This is how I started writing poetry. I would have a melody and then put a language to that melody and write.

I: How do you edit the things you write?

M: When I started I didn’t do any editing. I won’t write the poem down till I have it complete in my head, so I carry it in my head and edit it. It’s very convenient for this musical purpose because what you do is you repeat many times; it becomes like chanting, and when the poem is complete I write it down. Right now it’s different because I live in the States and I live in a English speaking community, I don’t feed off the language that I write in anymore – now it’s more of a paper process, but I still try and do as much in my head as possible. When I write things down it looks finished it’s claimed by paper already it’s hard for me to go back and edit anything because it looks finished.

I: Do you think that your poems ever lose anything in translation?

M: I think that people are divided into those who believe in translations and those who don’t, and I am a big believer in translation. I started translating other people’s poetry before I had to translate my own. When I lived in Warsaw I was on a scholarship in translation I was translating a Polish poet into Belarusian. I do think that poems lose in translation but at the same time they gain a lot, things that might not have been in the original but come out in a foreign language, because this is how the language of poetry is different than everyday language. In the poetic language, behind every word there is the whole mythology of the culture, so when you translate it only the word goes through – the mythology stays, but then there’s the mythology of another culture that comes in and it breathes something new into the poems. I know that my translations are different from the original poems in many ways but in many ways it’s not about better or worse; they gain things that they didn’t have. I have poems for example that were written as very straight forward, non-metaphorical poems that when translated into English become full of metaphors just because of the change in language.

I: Who are some of your favorite poets?

M: I generally prefer to say that I don’t like poetry because there’s so much bad poetry. And I’m not a person who reads it and likes it just because it’s a poem. I have my demands too. So I don’t like poetry in general, but I like certain poems; and for me I don’t really distinguish between poetry and prose – you know I come from a culture growing up on Russian poetry, like Pushkin, and Akhmatova, Mayakovsky, Tsvetaeva. Those poets were read the way people here read short stories and novels. So for me it’s not about if it’s a poem or if it’s a novel or a piece of prose – it’s about the quality. I don’t know if it would be worth naming any names. I got into Polish poetry and I think this is my favorite poetry – the generation of the sixties and seventies in Poland – and they’re very popular here. They’re very well translated, I would say: Szymborska, Milosz, Zagajewski, Baranczak – he’s hard to translate because he plays with the language a lot. But still, he’s interesting.

I: So you mentioned that you were going to be a musician; what instrument did you play?

M: I started to be an accordionist. I think for over eight years.

I: So is there anything you could say to young aspiring poets?

M: Yes, I always say the same thing, what I was told many times: read, read, and read. The more you read the better it is for you. And read a lot of very good literature – don’t be afraid of big thick serious books. This will help you to raise your own demand of yourself. When you have doubts about a poem don’t think ‘I’m just seventeen years old’ – just ask yourself if Robert Frost wrote it, would he be okay with it? This is my approach.

Tuesday, April 1, 2008

Varanasi by Austin Ryer

“Why, thank you very much,” I slurred, weakly attempting an Elvis impersonation. Of course he laughed, and went so far as to say I sounded like Elvis as well.

It was not often that I found myself wandering into an unknown city looking for some location based solely on a stranger’s recommendation. However, earlier we had learned that “Ghats” were holy places on the Ganges where a tributary joined the river, and so we followed the old man’s advice. After lunch at a nearby Pizzahut, I and three others caught an auto-rickshaw and showed the driver the name of the Ghat; its pronunciation was way beyond any of our simple knowledge of Hindi. The driver gave us a price, but told us he couldn’t go the whole way because it was closed to vehicles; we would have to walk some of the way. More hesitant now, we still agreed, and entered the rickshaw.

The auto-rickshaw was three-wheeled and about the size of most refrigerators turned on end, shaped into a rounded V. In front was a t-shaped handlebar used on motorcycles, and a small bench seat for the driver. In back, as the vehicle widened, there was a larger bench seat meant for three passengers though I’ve seen many more than that in rickshaws. It had a roof and windshield, which offered some protection, though it had no doors or sides. I sat in front alongside the driver, though half of me stuck outside, narrowly missing passing traffic. Behind me, on the bench, were my three friends, Julia, Dan, and Will, each lost in their own thoughts. After riding through thick traffic for about fifteen minutes, the driver finally pulled to the side, and let us out.

We found ourselves on a main road, with a solid division between incoming and ongoing traffic. Periodically, a side road or alley broke the endless line of buildings on either side. Accompanied by hand gestures to augment his weak English, our driver had told us that to get to the Ghat we had to walk straight for a while and, after three somethings, turn left onto another road until we saw something tall, and then to maybe take a right.

Almost immediately lost, we stopped to ask a man sitting on a cart for directions.

“Excuse me sir, do you know how to get here?” we showed him the paper with the name of the Ghat on it.

“Uhh… no angles?...“ We assumed he meant that he didn’t speak English. Turning to leave, we heard him say something in Hindi to a man passing by. The man stopped, looked at us, and quickly introduced himself.

“Hello,” he said in barely accented English, “can I help you get somewhere?”

He was young, maybe in his early twenties, and wore a white long sleeved shirt with a purple sweater tied around his neck. Though he looked flamboyant, he also looked well off, dressed in western clothing. To us, this meant that he didn’t need our money, and therefore would probably not try to steal from us. That, as well as the fact that we were already far within the city and had no idea where we were, lead us to trust him; we were probably safer with him than on our own.

Raz lead us into what we later learned was old Varanasi. This section of the city is comprised of thin alleyways crowded with people, cows, and debris, overshadowed by high buildings on either side. This deep into the city, even shopkeepers were indifferent, and didn’t chase after us to sell their goods. In this area, everything was built for purpose. Beside countless silk and spice shops there were small restaurants serving chai to passing customers. Religious buildings lacked the grand archways and gates of other holy buildings. Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist temples blended into the city, with nothing other than occasional statues of deities separating them from the cafes and homes next to them. I do not know if we ever reached the Ghat the old man recommended, but we saw more. We saw an Indian city thousands of years old that still operated under the same principles as those of its founders and builders. We saw a life not prepared or watered down or expectant of foreign eyes. We saw life in this city as it simply was, with nothing to distract from the work that had to be done to survive.

Raz, like the old man at the hotel, had lived in Varanasi his whole life. However, Raz was different than most strangers we had met before. He was a perfect example of western culture intruding upon Indian traditions. As we walked, he asked us if we had seen a show aired on the BBC network a while back, because he had been in it. He knew perfect English and dressed in the western style, but as we learned later, Raz worked in a silk shop with his family, a small family owned business passed on for several generations, located in old Varanasi.

We asked him, “But why are you helping us? There must be somewhere else you could be besides showing us around the city?”

“Karma. This is good Karma, helping strangers, and it will help me in my next life. Besides, it’s my day off at work, why not show you around? It gives me something to do, yeah?”

We were not far into the city, however, when we were stopped. As we passed a police checkpoint, an officer called us over. He wore the standard tan uniform of the Indian police, and had a long brown rifle slung over his right shoulder. He was slightly overweight and wore a constant smirk, as if he enjoyed harassing foreigners like us, and did it often. He pulled Raz aside, but told us to go on. However, we were now in the city, and would be even more lost than when we were on the main road. Eventually we convinced the officer to let us go on our way, with Raz leading us. As we walked away, Raz thanked us.

“If you hadn’t helped, they would have kept me there for hours. They see sometimes Indians leading foreigners around the city, pretending to be tour guides and then charging very high prices later. The police are corrupt though, and would’ve demanded that I admit to being a guide or until I bribe them. Why should I say I’m something that I’m not? It’s not right, I will not lie. I have the right to go where I want, and help who I want.”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)